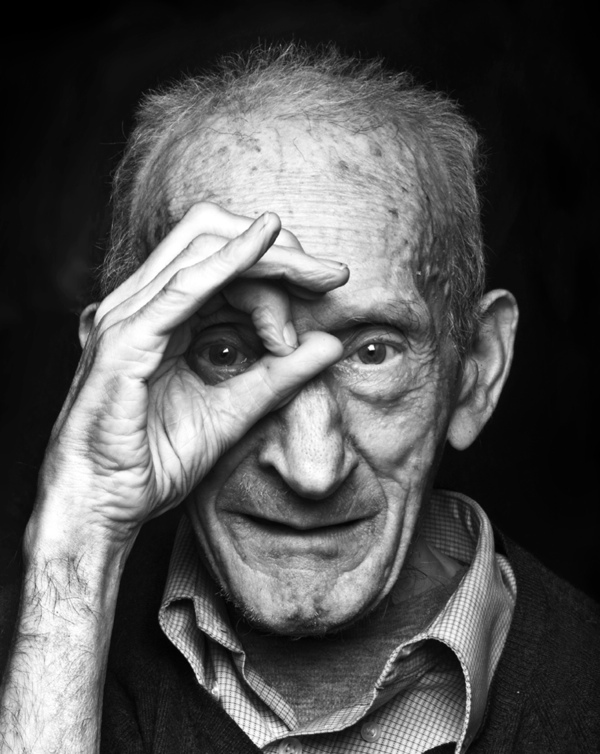

Today it is my pleasure to publish the story of Martin White, one half of the charismatic partnership with Philip Pittack that is Crescent Trading, operators of Spitalfields’ last cloth warehouse.

![white_0006]()

Martin White, aged two in 1933

“That’s the difference between Philip & me,” explained Martin White, articulating the precise distinction between himself and his business partner Philip Pittack, “He’s a Rag Merchant, whereas I am a Textile Consultant. I understand textiles, I know about suitings and have been dealing in them since 1946. Our different specialities complement each other.”

Famous for his monocle and pearl tiepin, as well as his unrivalled knowledge, Martin White is one half of the duo known as Crescent Trading, possessing more than one hundred and twenty years of experience in the business between them. While their continuous comedy repartee has won them a reputation as the Mike & Bernie Winters of the textile trade.

In particular, Martin is known for his ability to make an offer on a parcel of textiles on sight. “Very few people know how to do it,” he admitted to me. “These days, Philip & I go on a buying trip twice a year, but in the past I used to go buying every day.” Martin’s story reveals how he acquired his remarkable knowledge of textiles, developing an expertise that permits him obtain the quality fabrics for which Crescent Trading is renowned.

“My father, William White, was a leather merchant but he also had some boot repair shops and, because he was a bit of mechanic, he rebuilt boot repairing machines. And that’s what he wanted me to go into. We lived in a very nice house in Shepherd’s Hill, Highgate, but unfortunately my father was diabetic who didn’t believe in conventional medicine. He was a herbalist and he became very ill in his forties and died at forty-six.

I started work at fourteen for my two uncles, Joe Barnet & Mark Bass (known as Johnny,) at their shop in Noel St off Berwick St in 1946. I was a little boy who didn’t know anything and in those days fabric was rationed and very hard to come by. Joe used to go up north and he had contacts in Manchester who used to get him stuff from the mills. It was a tiny shop and everything we got we sold immediately. They were making thousands every week and I was getting two pounds a week for carrying the fabric in and out. I used to like touching the fabric and that’s how I learnt about it.

While I was there, my father died and another of my uncles, David Bass, came to see my mother and he said he would take me to work for him and give me a wage, so she wouldn’t have to worry about me. But when the two uncles I was already working for heard this, Joe Barnet sent his wife Zelda to my mother to say that, if I worked for David, I would take all their customers from Noel St and it would ruin their business. So Joe Barnet told my mother he would look after me. He had just formed an association with a government supply business in Bethnal Green and he asked me to go down there and watch because he didn’t trust them, and that was my job.

So the first Friday came and he gave me five pounds, that was my wages. The following week, I found a parcel of cloth for sale in Brick Lane and I bought three thousand yards at a shilling a yard and I sold it for three shillings and sixpence a yard. The next Friday, Joe gave me fifteen pounds but I realised I had no chance of furthering myself with him, so I left and started working with another boy of my own age, Daniel Secunda. We were fifteen years old. We had no premises. We used to stand by the post at the corner of Berwick St, and people came to us with samples and goods to sell. We took the samples and sold them, and we made a good living between the two of us. We were young and we were carefree.All the money we earned, we spent it. We were happy. We went out every night. And that lasted for about three years, before the business got hard when rationing ended.

Then I met a guy who wanted to go into business properly with us, Pip Kingsley. He took premises in Berwick St and formed P. Kingsley & Co. After a while, it became apparent that while Danny was a very good-looking and likeable fellow, I was the worker out of the two of us. So Kingsley got rid of Danny and rehired an old job buyer who had retired, Myer King, and we started working together. He was an Eastern European, a very big man who couldn’t read or write. He had the knack of job buying ‘by the look.’ He’d go into a factory and make an offer for everything on the spot. This method of buying was different to anything I had ever seen but it worked. By working with him, I learnt what to do and what not do. And that knowledge was the basis of how I did business from then on.

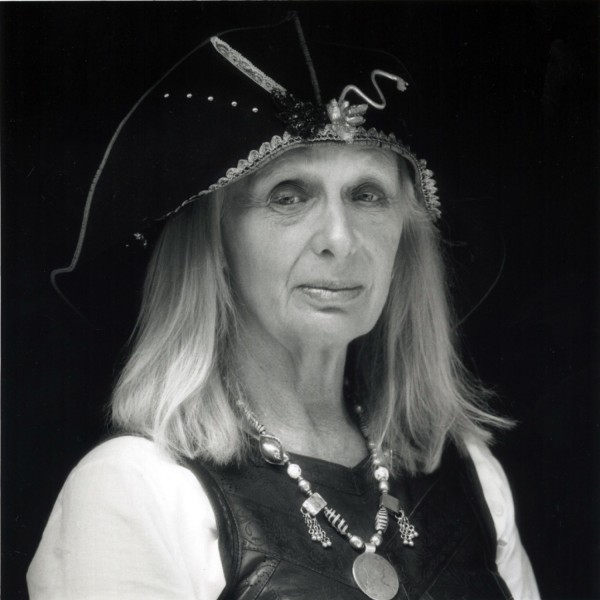

I was happy working with Kingsley & Myer, but then I met my wife to be, Sheila, and I decided that I wanted my share of the money that my father had left in trust for my younger brother Adrian and me when we were twenty-one. I wanted to get married, and Sheila had been married before and she had a little boy. She was very beautiful. She’s eighty-five and she’s still beautiful.

My brother Adrian was known as Eddie and, at the age of eleven while my father was dying, he contracted sugar diabetes, so they were both in hospital. In the next bed to him was George Hackenschmidt, a boxer who had done body-building and my brother became interested in this. It was a very sad thing, my dad died when they were both in hospital and an uncle said to Eddie, ‘When you get out, I’ll buy you anything you want,’ to make him feel better. So Eddie said, ‘I want a set of weights.’

It was back in 1945, Eddie was twelve and he got one hundred pounds worth of weights and equipped a gym in our garage, and he started doing these workouts in the American magazines that George Hackenschmidt had given him. Eventually, he became Charles Atlas’ body. They would take the head of Charles Atlas and put it on a photo of my brother in the adverts for body-building.

When we broke my father’s trust fund, Eddie was twenty-one and we each received eight hundred pounds. My brother only lifted weights and sat in the sun, so I said to him, ‘What are you going to do with this? Give it to me and we’ll be partners, and I’ll do all the work and you can sit in the sun.’

Now, I wanted to get married to Sheila and her father was a textile merchant but her family didn’t like who I was. One of them was A. Kramer who happened to be Dave Bass’ solicitor and he phoned me up to warn me off her. So I told him what he could do, and Sheila and I got married in a registry office in 1955. Sheila’s little boy was four and her father, Lou Mason, didn’t want him to suffer, so he came to see me at my business and I showed him what I was buying.

Then he approached me one day and asked if I was interested in looking at a parcel of goods he had found in Wardour St at a lingerie company called Row G. So I went to see the parcel and made an offer of seven hundred pounds on sight. Lou said, ‘We don’t do business that way,’ and I said, ‘I’ll do it how I want to do it.’

The owner said, ‘No,’ but two weeks later I went back. He took the seven hundred pounds and it was all sold within two weeks for eighteen hundred pounds. My father-in-law said, ‘I’ve never seen anything like this. It’s wonderful, why don’t you come and work with me?’ I couldn’t say, ‘No,’ to my father-in-law. There was no option. I said to my brother, ‘We’ll have to part company and I’ll give you your money back.’ He never forgave me.

The very first deal that came along was Cooper & Keyward, they had a lot of rolls of suiting and it came to two thousand pounds. But when I asked my father-in-law for the money to buy it, he said, ‘I’m a bit short this week.’ I just about had the two thousand pounds so I laid out the money myself and took the goods, and my father-in-law was able to sell it to his customers. On Friday, I said to him, ‘I need forty pounds to take my wife out,’ and he said, ‘We don’t spend money that way!’ So I fell out with my father-in-law. It turned out, he didn’t have the money to pay me because his business was going bankrupt.

I went round to get my goods which were in the basement of a shop in Berwick St and my mother-in-law was in the shop. A cousin came out and said, ‘You’re going to kill her, can’t we meet at the weekend and sort this out?’ At the meeting, my father-in-law accused me of being a liar but my wife’s aunt, Joyce, knew him and said to me, ‘I believe you.’ I never was a liar. She said to me, ‘If I lend you a thousand pounds, can you make a living?’

In Berwick St, Johnny Bass was trying to sell his stock at the shop where I had started work. The Noel St shop was full of fabric and he’d offered it to several people but no-one could assess what was there. He wanted four thousand pounds yet, because of my knowledge, I was able to cut a deal for two thousand four hundred pounds. It was Friday night and he said, ‘Give me some money.’ He’d just come of out of the bookmakers and he was penniless. I had a hundred pounds on me, so I gave him that and I had to find the rest of the money.

I went to get it from Joyce but she was in hospital. So I visited her and she said, ‘My husband Bert will get the money for you,’ and on the Monday he came with me to pay Johnny. Joyce had a property in Mansell St and I filled it up with the fabric and started selling it every day from there. Joyce was coming over to collect money from me in her handbag. She was charging me one hundred pounds a week rent plus interest, so I realised she thought I was working for her now but it wasn’t a partnership in my eyes and I wouldn’t go along with it.

I told her I wanted premises in Great Portland St and I needed money for that. It was agreed and that’s what we did. It was called the Robert Martin Company – Sheila’s son was called Robert. I got Daniel Secunda back to work with me. It was 1956, I had my own shop at last. And that’s how I became a textile merchant.”

![white - Version 2]()

Aged two, 1933

![white_0008_2]()

Aged three, 1934

![white_0014]()

Aged five in 1936

![white_0006_2]()

At school in Highgate, 1936

![white_0013]()

![white_0004]()

At a family wedding in September 1939. On the left are William & Muriel White, Martin’s parents. Beside them is Joe Barnet, Martin’s first employer, and his wife Zelda.

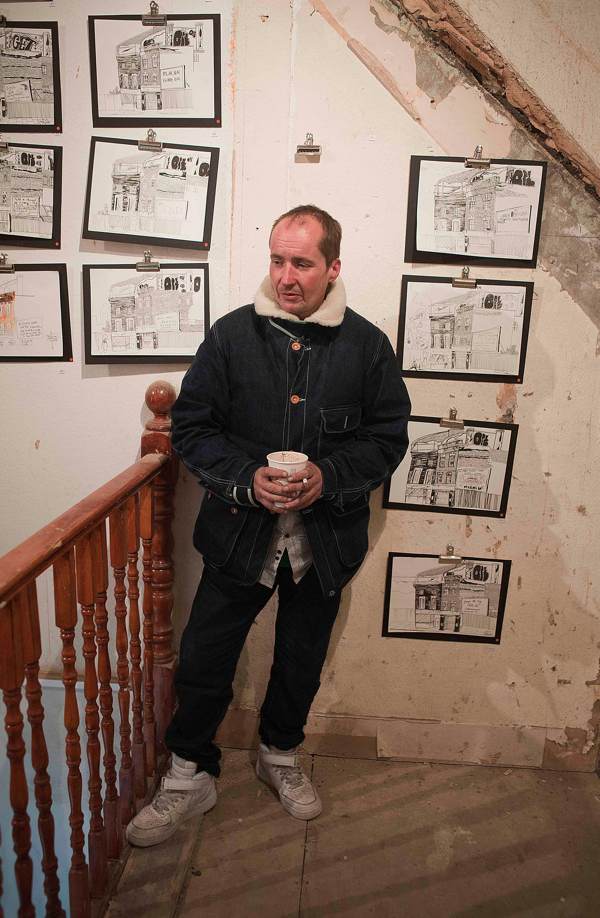

![white]() Martin’s brother Adrian (known as Eddie) who became the body of Charles Atlas

Martin’s brother Adrian (known as Eddie) who became the body of Charles Atlas

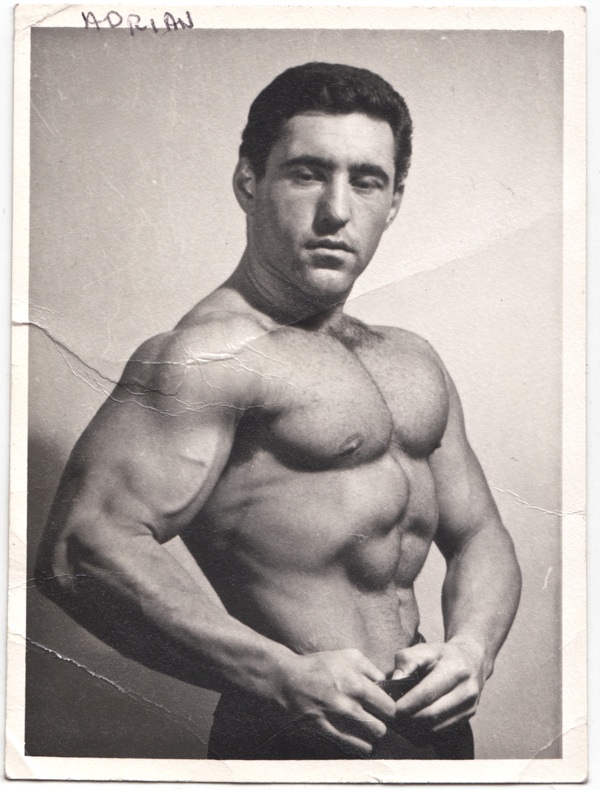

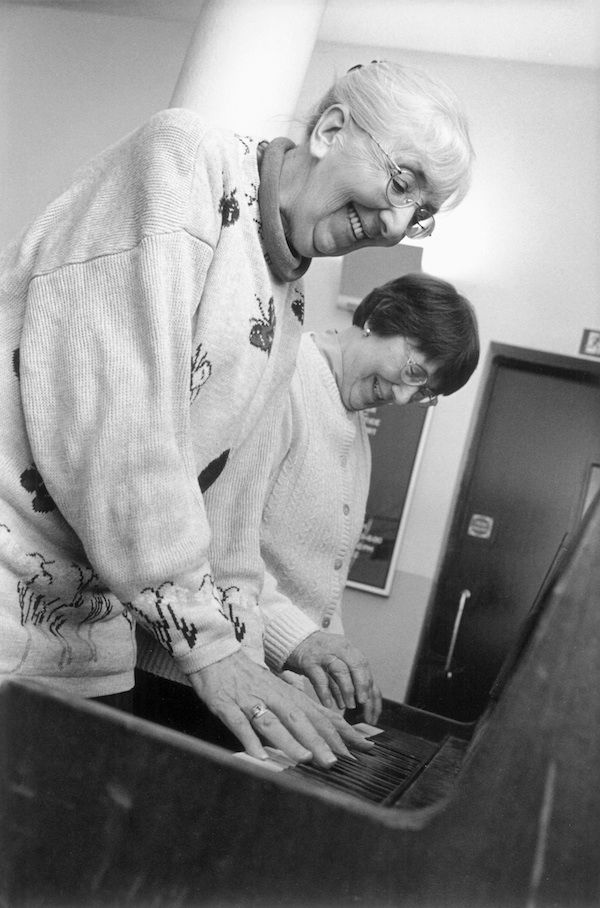

![white_0008]()

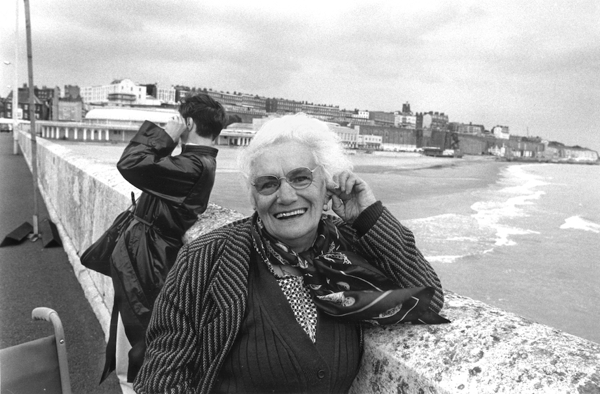

Martin White & Danny Secunda, his first working partner in 1956

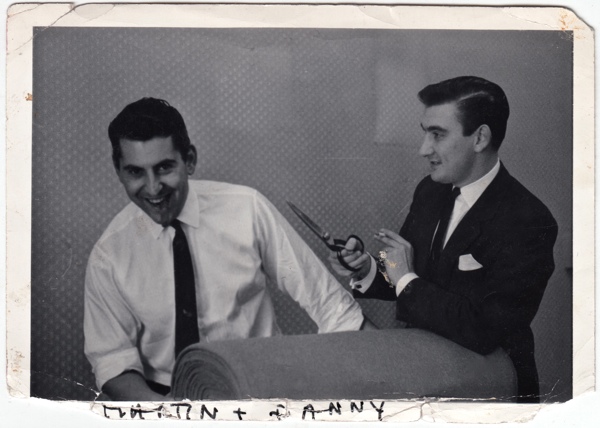

![img_80071]()

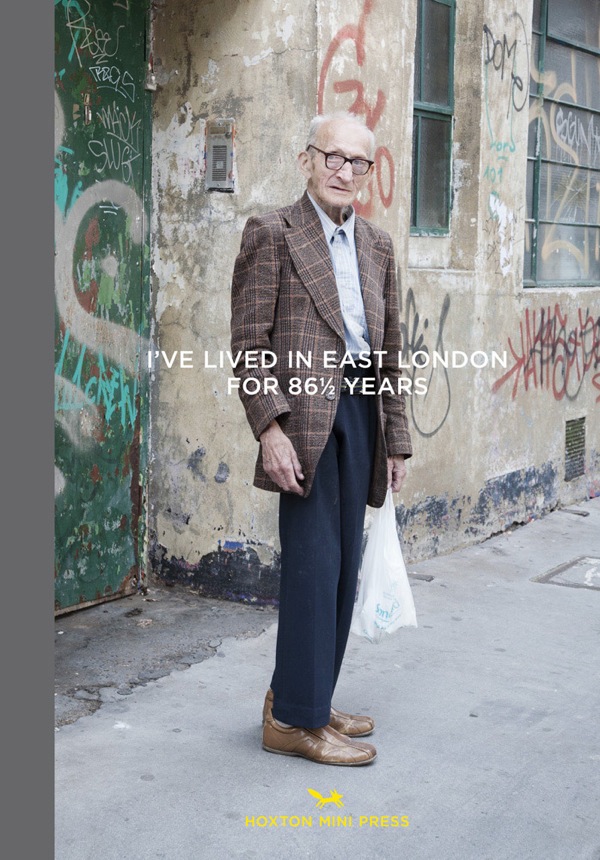

Martin White & Philip Pittack, Crescent Trading Winter 2010

Crescent Trading, Quaker Court/Pindoria Mews, Quaker St, E1 6SN. Open Sunday-Friday.

You may also like to read about

Philip Pittack, Rag Merchant

The Return of Crescent Trading

Fire at Crescent Trading

Philip Pittack & Martin White, Cloth Merchants

All Change at Crescent Trading