![IMG_2521]()

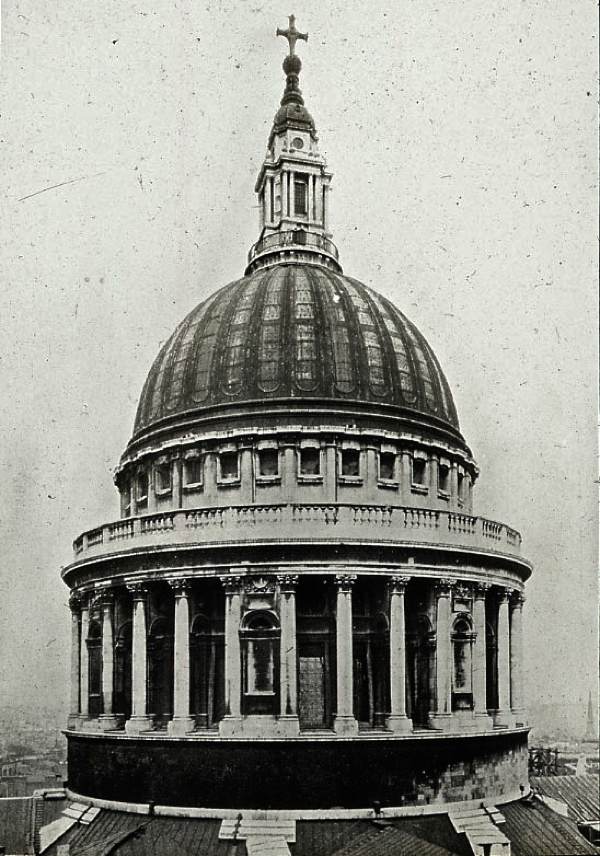

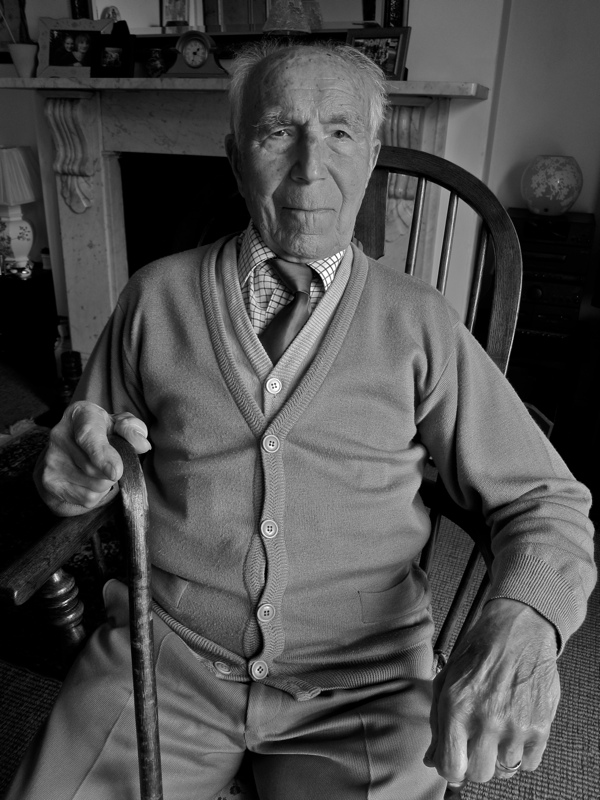

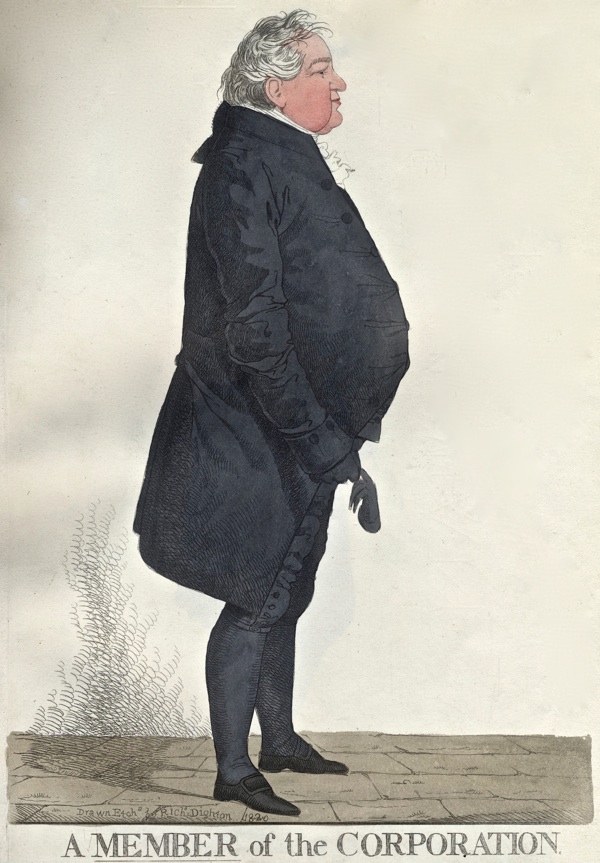

Bud Flanagan was born above his family’s fish & chip shop in Hanbury St

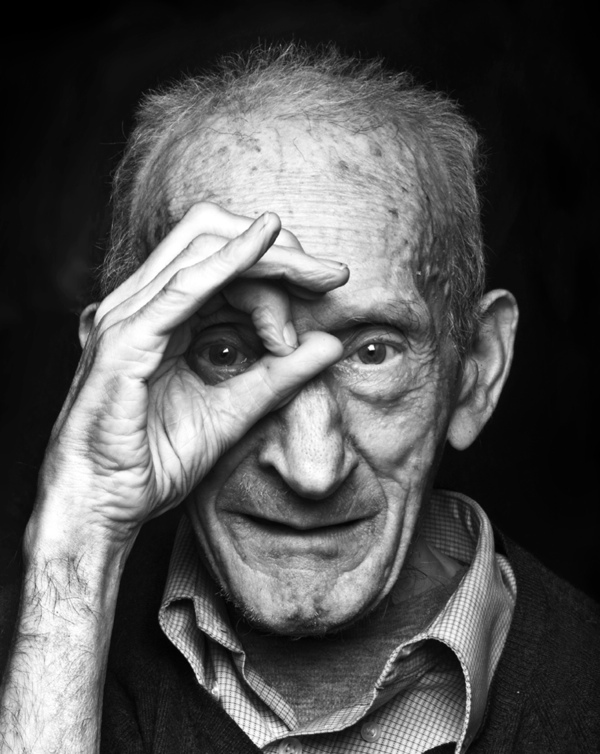

Today I publish reminiscences of Spitalfields written in 1961 by Bud Flanagan, the celebrated Music Hall comedian, part of the Crazy Gang and half of the legendary Flanagan & Allen double act. Born as Chaim Reeven Weintrop in 1896 into a Polish immigrant family who ran a fried fish shop in Hanbury St, Bud Flanagan began his performing career as a child in East End End Music Hall and came under the spell of street performers beneath the Braithwaite arches in Wheler St – that later featured in the song by which he and Chesney Allen are most remembered today, “Underneath The Arches.”

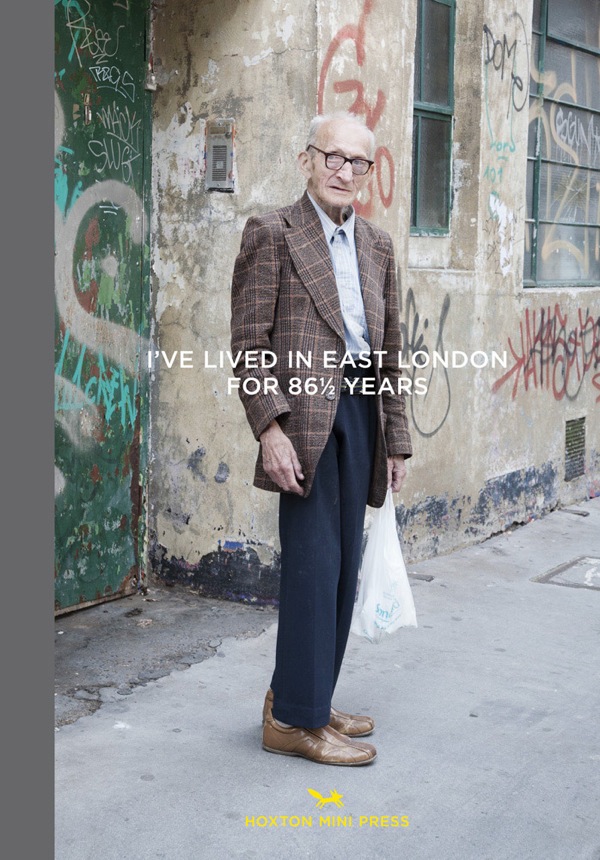

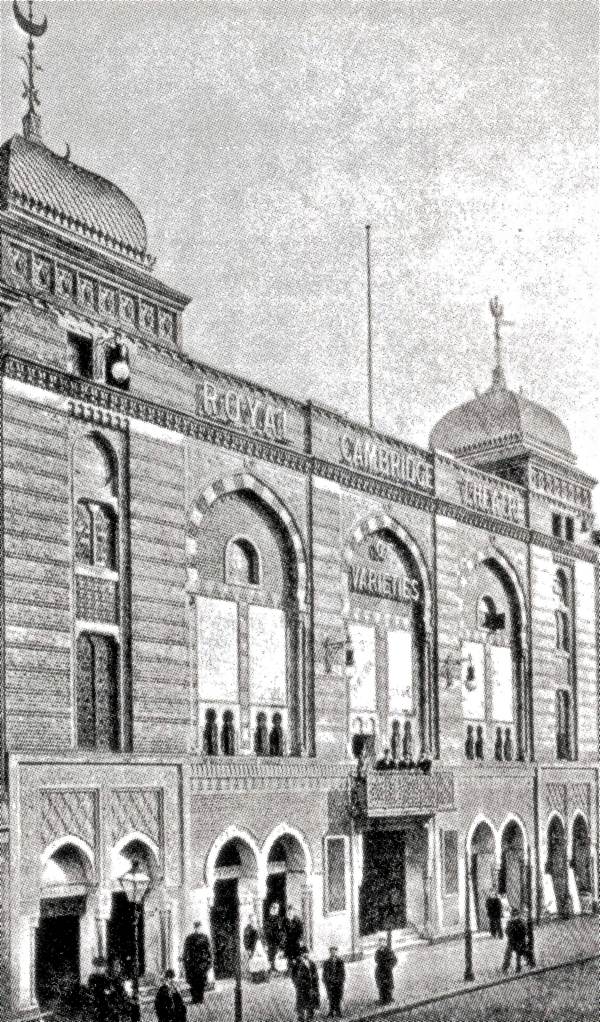

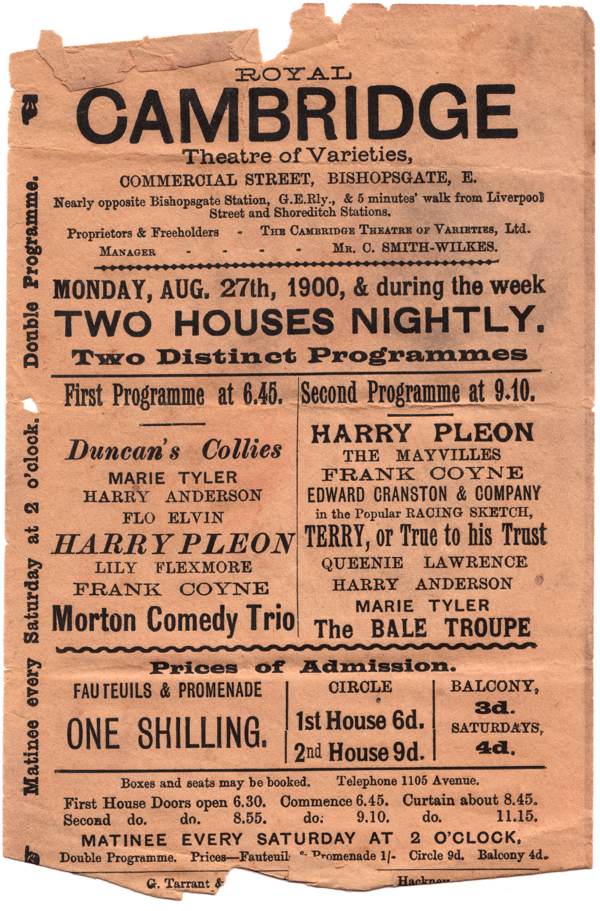

In common with Charlie Chaplin, who was his close contemporary and performed in Spitalfields at the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties in 1899 where Bud Flanagan became a Call Boy in 1906, he adopted the persona and ragged costume of the dispossessed, revealing pathos and affectionate humour in the lives of those who were seen as downtrodden and marginal.

“The labyrinth of streets that go to make up the district of Spitalfields are narrow and mean. The hub of my world was the churchyard or, as the locals called it, “Itchy Park,” after the doss house habitues who would sun themselves on the benches or low stone walls that surrounded the park. They would sit there every day, scratching, yawning and looking into space. The cemetery was old and derelict, but it was a reminder that at one time Spitalfields was the centre of the weaving trade because nearly all the tombstones bore the inscription, “weaver.” Most of them were dated 1790-1820 and a few were still upright. Several had fallen over and on our way to school we would hop, skip and jump over them.

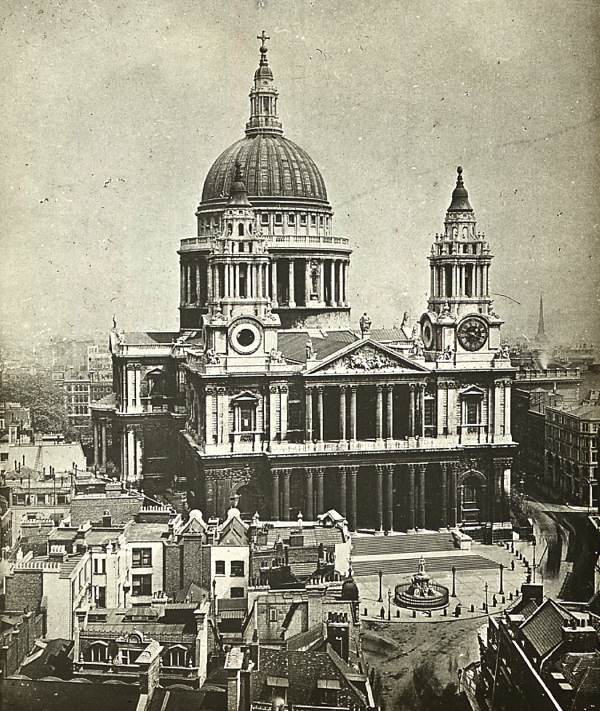

Hanbury St – where I was born – crawled rather than ran from Commercial St, where Spitalfields Market stood at one end, to Vallance Rd at the other, an artery that spewed itself into Whitechapel Rd at the other. On one corner stood Godfrey Philips’ tobacco factory, with its large ugly enamel signs, black on yellow, advertising “B. D. V. ” – Best Dark Virginia. It took up the whole block until the first turning, a narrow lane with little houses and a small sweet shop.

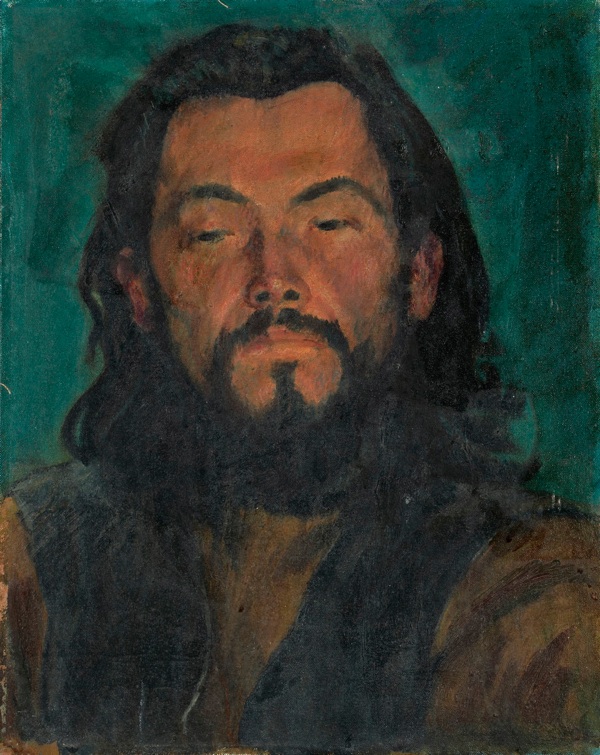

On the next corner was a barber’s shop and a tobacconist’s which my father owned. Next door to us was a kosher restaurant with wonderful smells of hot salt beef and other spicy dishes, then came the only Jewish blacksmith I ever met. His name was Libovitch, a fine black-bearded man, strong as an ox. From seven in the morning until seven at night, Saturdays excepted, you could hear the sound of hammer on anvil all over the street. Horses from the local brewery, Truman, Hanbury & Buxton, were lined up outside his place waiting to be shod.

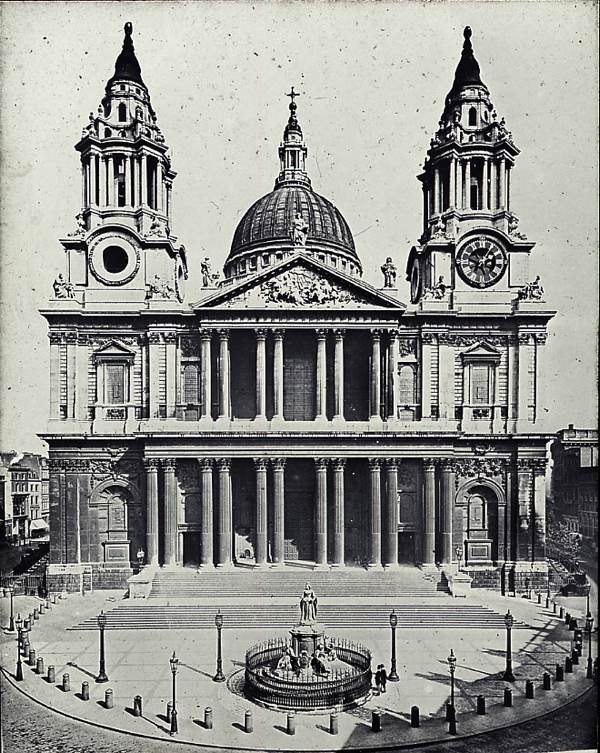

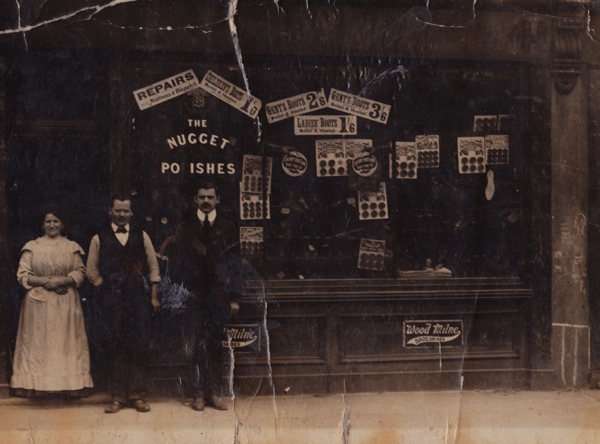

Then came another court, all alleys and mean streets. Adjoining was Olivestein, the umbrella man, a fruiterer, a grocer, and then Wilkes St. On one side of it was a row of neat little houses and on the other, the brewery taking up streets and streets, sprawling all over the district. On the corner of Wilkes St stood The Weavers’ Arms, a public house owned by Mrs Sarah Cooney, a great friend of Marie Lloyd. She stood out like a tree in a desert of Jews. Stapletons depository, where horses were bought and sold, was next door to a fried fish shop, number fourteen Hanbury St where I was born. Next to that was Rosenthal, tailors and trimming merchants, then a billiard saloon, after that a money-lenders house where once lived the Burdett-Coutts.

Hanbury St was a patchwork of small shops, pubs, church halls, Salvation Army Hostels, doss houses, pubs, factories and sweat shops where tailors with red-rimmed eyes sewed by the gas-mantlelight. It was typical of the Jewish quarters in the nineties. The houses were clean inside but exteriors were shoddy. The street was narrow and ill-lit. The whole of the East End in those days was sinister.

Neighbours who slaved hard at their businesses left the district (once they began to save money) and moved to what was then nearly the country – Stamford Hill, a suburb in North London that was rapidly becoming a haven for the successful Jewish businessman and artisan. It was only a penny tram ride from Spitalfields to Stamford Hill, but often it took a lifetime of savings and struggle to make the move. When they got there, most were like fish out of water, sad at the parting from old friends and missing the old surroundings. Homesick, they even came all the way back to the East End to do their shopping. Eventually they were joined by their old neighbours, who too had crossed into the Promised Land.

Not everyone was lucky enough to move and among the stay-puts were my parents. First of all, they couldn’t afford it, and secondly the fish shop and barber’s made barely enough to keep a big family of five daughters and five sons. I first saw the light of day, if kids are not like kittens, on 14th October 1896. My parents, who had been in the country for years, could hardly be understood when speaking English. When a child was born the Registrar wrote down a rough phonetic version. I was named Chaim Reeven, which is Hebrew for Reuben and became Robert. My father’s name was Weintrop which the Registrar abruptly changed to “Winthrop.”

Ours was a district where the weak went to the wall and you had to keep your eyes open. When my father opened his fried fish shop, the salt cans were chained to each table and to the counter. But, as in every Jewish home, education was important and apart from ordinary school, I attended cheder for Hebrew lessons three nights a week. The East End at that time had several boys’ and girls’ clubs. I joined the Brady, named after a street tucked behind Hanbury St. We had ping pong, gymnastics and chess and it was a treat to get off the streets into the warm and play games without having fights, of which I had my share.

I became interested in conjuring and used to walk to Gamages in High Holborn and look longingly at the tricks they sold but without the coppers to buy them. To raise the money, I took a job as a Call Boy at the Cambridge Music Hall in Commercial St at the age of ten. The job was very handy. When the pros wanted fish & chips – and they wanted them every night – I went to my father’s shop. There were no wages, only tips, but I was soon able to buy my tricks and those I couldn’t afford I made. When the fish shop was closed on a Sunday, I let the kids in for a farthing, charging the older ones a ha’penny and gave them a show. Mothers would bring their children and soon there was a good sprinkling of grown-ups.

I was making a local name until one Sunday a big rat came out of nowhere and evil-eyed the audience. There were screams and before you could say “Abracadrabra!” the place had emptied. It did not do me any harm but word soon spread, “There are rats in the fish shop,” which was not surprising as we were next to a horse repository with its hay and oats. There wasn’t a morning when the traps had fewer than three or four big ones. I used to watch in fascinated horror as they drowned in a deep tub of water.

That was in 1908, the year the Music Hall artists decided to strike. Being only a call boy, I wasn’t worried by the strikers who picketed the Stage Door trying to persuade the non-strikers to come out. They weren’t really rough, only to the extent if grabbing a bottle of stout or some fish & chips out of my hand and asking whom they were for. I’d tell them and the lot would finish in the gutter. With tears in my eyes, I would run down the long corridor to the Stage Manager at the Prompt Corner and let him know what happened, but mostly I was left alone.

The management who owned the Cambridge also ran the London Music Hall in Shoreditch High St and Collins in Islington. The three halls were known as the L.C.C. – London, Collins & Cambridge. It was at the London that I made my first stage appearance.

Every Saturday at the 2:30pm they had an extra matinee when the acts worked for nothing. The place was packed with a good sprinkling of agents out front to see the fun and maybe pick up an act. The audience were like wolves, all ready for their Roman holiday, booing and jeering at anything they didn’t like. The Stage Manager in the corner, with his hand on the lever, was only too happy to join in the fun and bring down the curtain. The orchestra played with one eye on the music and one eye on the coins or rubbish that would be thrown at some unlucky act on the stage.

I was nearly thirteen and not too bad at manipulating cards and doing other tricks when I went to the London one Saturday afternoon together with my conjuring table and other props. I gave my name as Fargo, the Boy Wizard. The first prize was fifty shillings and a week’s work at the theatre.

The matinee produced some sixteen acts, most old-timers anxious for a week’s job and the cash, together with beginners who had never done a show outside their front room at home. The audience was as rough as ever and, at about 3:30pm, I came on. Being a kid, they were sympathetic towards me, but I was nervous and messed up my first trick. I had to pour water into a tumbler to make it beer and then pour it into another tumbler to make it milk. Alas, in my excitement, I had forgotten to smear the glasses with chemicals and instead of applause came jeers. Foolishly, I then asked to borrow a bowler hat. A bowler in Shoreditch! There was no such thing in the whole of the East End, let alone at the London Music Hall, Shoreditch. Well, I couldn’t do the trick with a cap and had to drop that illusion.

That started them off. Friends were in front, fellow scouts and Brady boys, but I got the bird. The curtain was rung down. I collected my props and and sneaked out of the Stage Door. There stood my father, waiting for me. A stinging right-hander caught me across the face, my ear is twisted, and I heard him saying, “I’ll give you, working on the Sabbath!” I was punched and pushed all the way home. My props lay somewhere in Shoreditch High St. I never saw them again.

I was growing to be a big boy but still working at the Cambridge. On my one free night, Sunday, we would go to the home of a man named Alf Caplin to sing songs and enjoy ourselves. He was a great pianist and one Sunday we decided to form our own quartet. We rehearsed an act and soon landed an engagement at a Dutch Club called “The Netherlands” situated in Bell Lane. The small stage was at the far end of the room and every Sunday there would be five acts, whose pay packet averaged about five shillings each. Dutch clog dancers and yodellers were the favourites. We called ourselves “The Four Hanburys, Juvenile Songsters,” and as there was plenty of club work in London on Sundays, we hoped to be recommended to other clubs.

We opened in harmony and it was nice bright tune, but after about eight bars the harmony was lost and we were all singing the melody but not not in tune. That was the first and only time I have ever been hit by a Dutch herring. I don’t know whether you have seen one but the brine and skin stick to your fingers when you eat them. So you can imagine what it does when one lands on your face. Several more came and that was the Four Hanburys finale.

Competitions were regular feature of the Music Halls and nearly every week the Cambridge had one. A singer, who also ran a competition, was a nice woman named Dora Lyric, married to a successful agent, Walter Bentley. Well, Dora was appearing at the Cambridge and also running the competition. One night there was scarcity of entrants. In desperation, her husband poked me with his stick and said, “Boy, you go on and sing one of Miss Lyric’s songs.” “Who me?” I echoed, trying to hide my eagerness and looking at the Stage Manager who nodded, “Yes.”

Dora Lyric had a popular song, “If you want to be a Somebody,” and I decided to sing that one. Being the only boy in the competition at that house, I won hands down and was picked for the final on Friday night. At the final, there were ten competitors who had won their respective heats, but I won the competition and that precious thirty shillings.

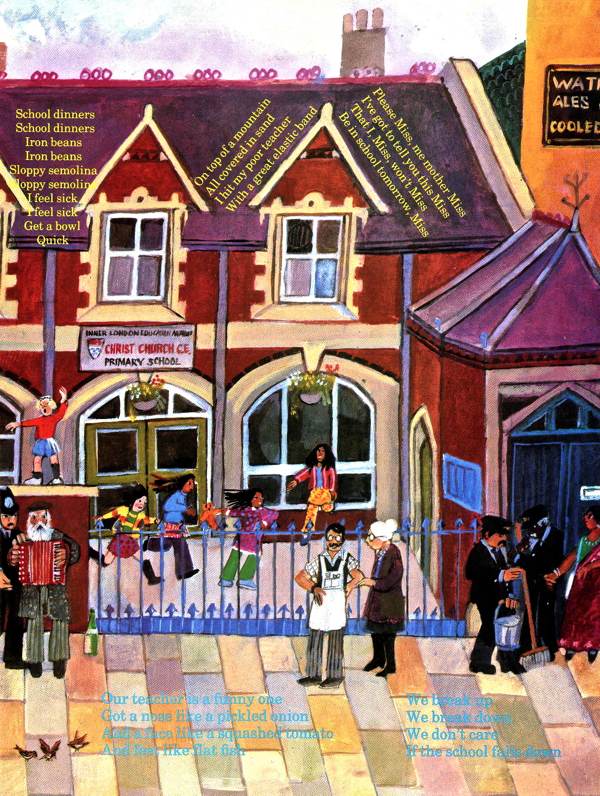

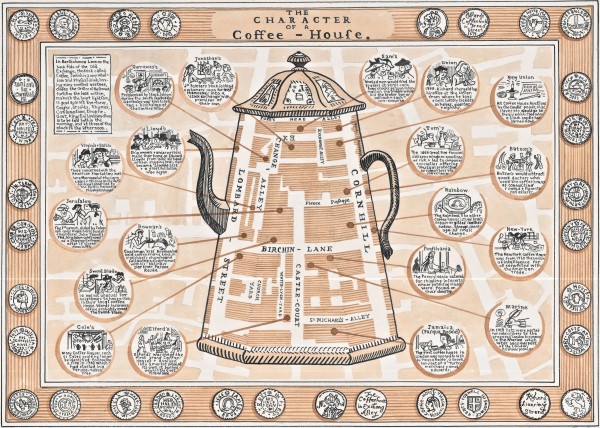

American acts had been coming over to play the Halls for some time now and they fascinated me with their new style and approach to the public and especially by their way of talking. British artists soon cottoned on and before time there was a spate of imitators of American-style acts, watching them from the gallery and then going round the corner to the Arches – a long street under a railway which carried the mainline to Liverpool St Station and ran from Commercial St to Club Row, a Sunday market where they sold mostly dogs and canaries. There the pros would practise to mouth-organ acompaniment, night after night, until they had copied the Yanks most intricate steps.

I became so interested in the Americans that I decided, after talking with them and reading about the States, that I must go there one day. The year was 1910, I was still at school and had about three months to finish. We were still in Hanbury St and on the day before I was fourteen, I made up my mind I was going to the New World, the place my dad tried to get to and never did. But my first impression of New York was a sad shock – Hanbury St, Spitalfields, seemed like the Mall in comparision…”

![flanagan_0001]()

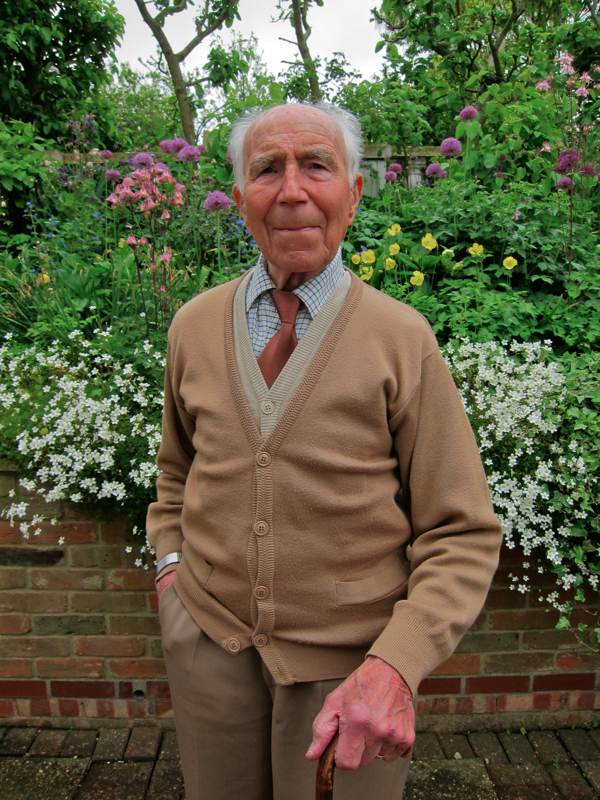

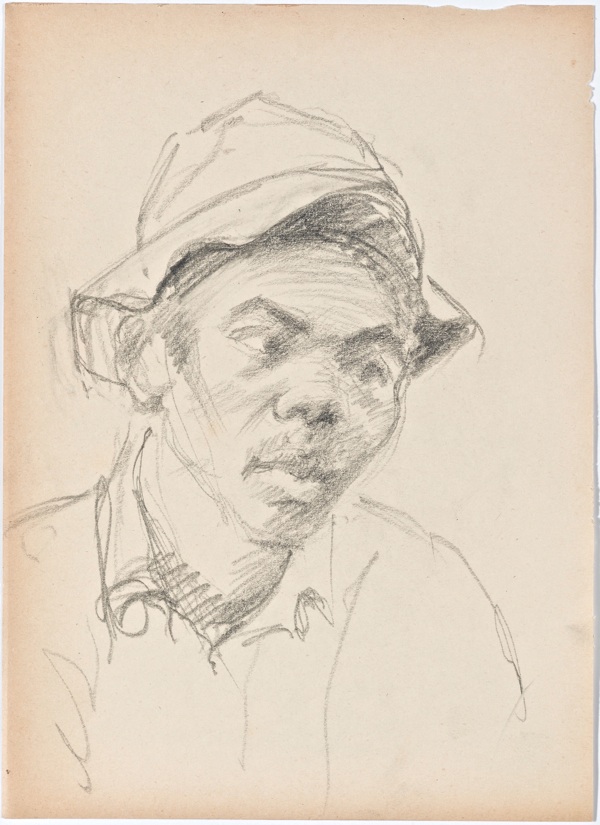

Chaim Reeven Weintrop (later known as Bud Flanagan) at the age of two with his brother Simon

![IMG_2523]()

The red premises are the former fish and chip run by Bud Flanagan’s family, where the young comedian staged magic shows on Sunday afternoons until a rat appeared and put a stop to it. The yard to the right was where Libovitch the blacksmith shoed the horses from the Truman Brewery.

![flanagan_0002]()

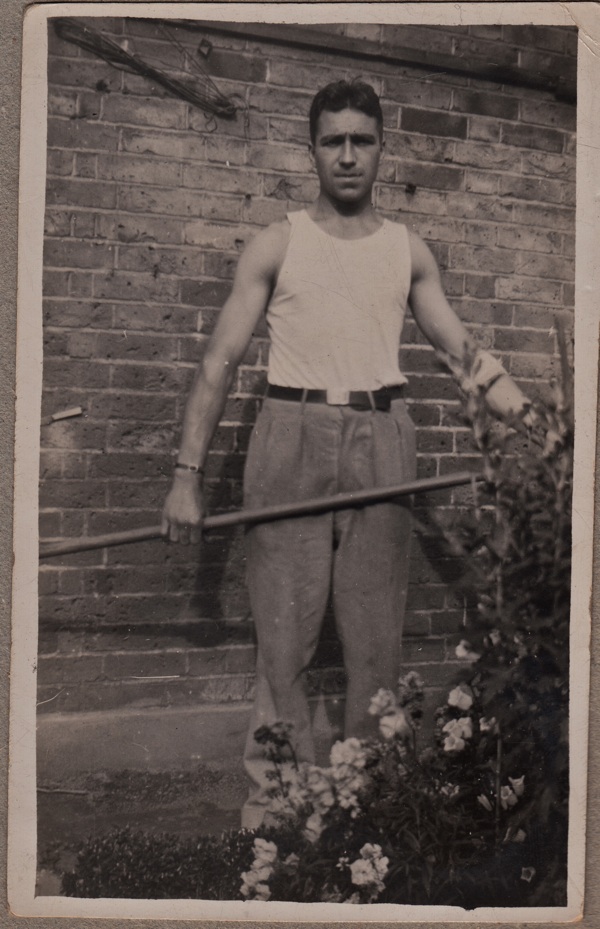

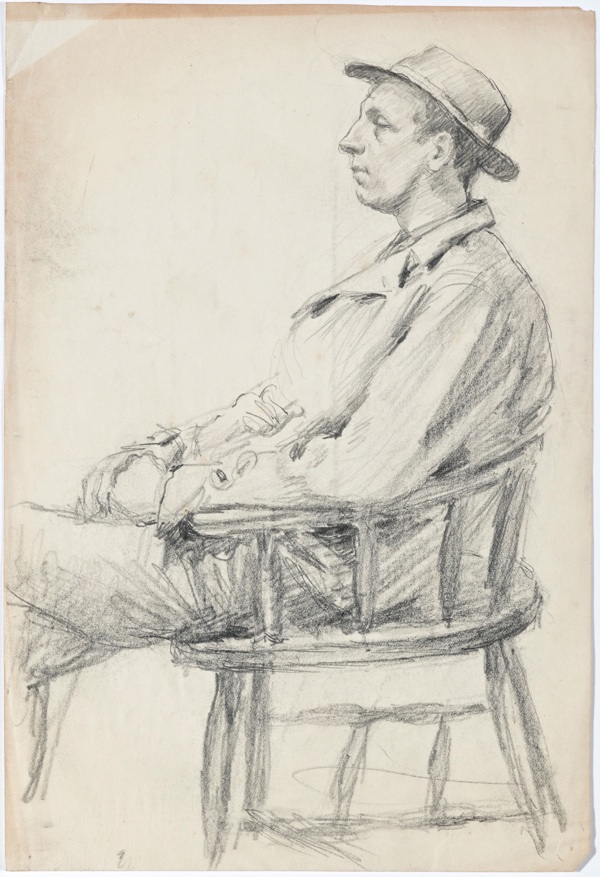

Wolf & Yetta Weintrop fled Poland in the eighteen-eighties hoping to get to New York but settling in Spitalfields where they ran a fish & chip shop in Hanbury St

![IMG_2531]()

“On one corner stood Godfrey Phillips’ tobacco factory, with its large ugly enamel signs”

![IMG_2530]()

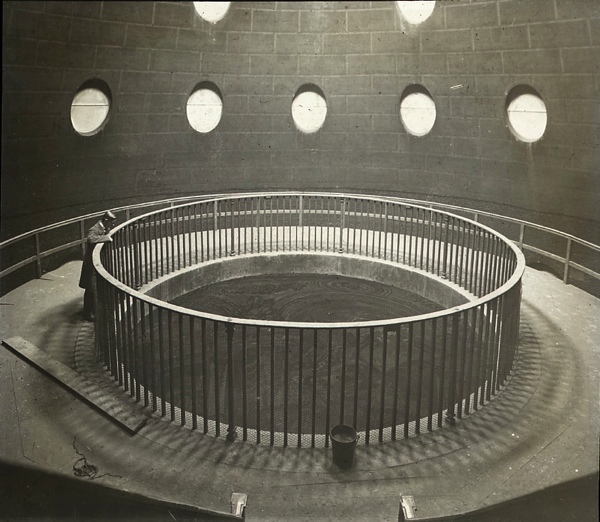

“Stapletons depository, where horses were bought and sold”

![Image195]()

Cambridge Theatre of Varieties in Commercial St where Bid Flanagan was a Call Boy at ten years old

![betts_0020]()

Handbill for Cambridge Theatre of Varieties

![flanagan]()

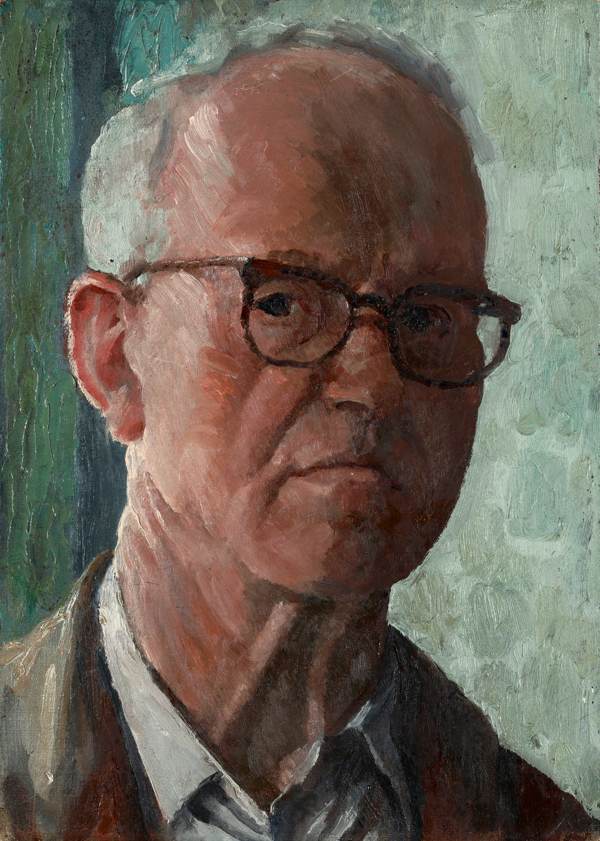

Bud Flanagan at the peak of his fame

![IMG_2557]()

“The Arches – a long street under a railway which carried the mainline to Liverpool St Station and ran from Commercial St to Club Row, a Sunday market where they sold mostly dogs and canaries. There the pros would practise to mouth-organ acompaniment, night after night, until they had copied the Yanks most intricate steps.”

![flanagan_0005]()

.

Underneath the arches

I dream my dreams away,

Underneath the arches

On cobble stones I lay,

Every night you’ll find me

Tired out and worn,

Happy when the daylight comes creeping

Heralding the dawn.

Sleeping when it’s raining

And sleeping when it’s fine,

I hear the trains rattling by above,

Pavement is my pillow

No matter where I stray,

Underneath the arches

I dream my dreams away.

Underneath the arches

On cobble stones I lay,

Every night you’ll find me

Tired out and worn,

Happy when the daylight comes creeping

Heralding the dawn.

Sleeping when it’s raining

And sleeping when it’s fine,

I hear the trains rattling by above,

Pavement is my pillow

No matter where I stray,

Underneath the arches

I dream my dreams away.

.

Lyrics by John Farnham

.

[There is a video that cannot be displayed in this feed. Visit the blog entry to see the video.]

You may also like to read about

Chaplin in Spitalfields & Whitechapel