The second of seven stories by Writer & Anthropologist Delwar Hussain, author of Boundaries Undermined, who grew up in Spitalfields

![EAST END FOOTBALL SERIES - by JEREMY FREEDMAN 2014_2]()

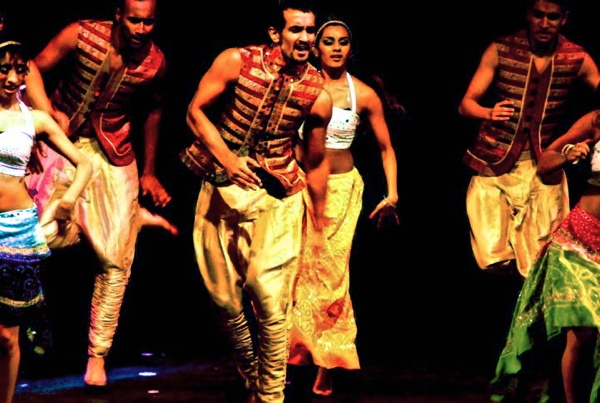

In the early seventies, finding themselves barred by whites-only football teams, a group of undeterred British Bangladeshi players came together and formed their own team. Today that team, the Mohammedan Sporting Club, has become one of the most successful sides in the British Bangladeshi Football League, with the current generation of players winning major local and national titles, and even playing in international tournaments.

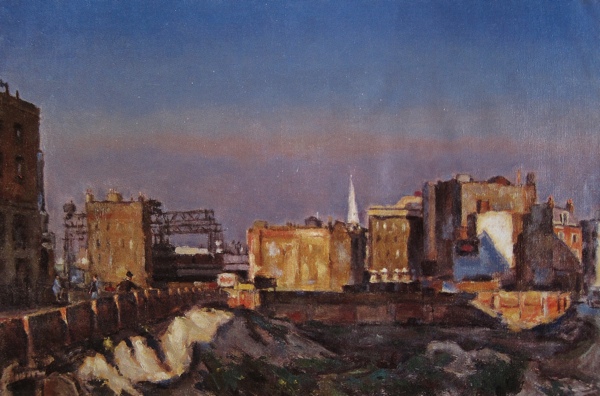

It is Sunday morning in Bartlett Park, Poplar, which is surrounded on all sides by housing developments with Canary Wharf looming large over the horizon. I have come to see the Mohammedans play. In their white and blue kit, the members are all shapes, age and sizes. It is no longer dominated by Bengali players, reflecting the changes in the East End. Together, the team looks determined to win the match.

From the first blow of the referee’s whistle, the rivals – another local side – the Hackney Probashis, appear stronger and are on the offensive, outmanoeuvring the Mohammedan’s defences. The ball is passed quickly and skilfully between the players, all in red. A deflection here, a twist there. At one point, the ball flies into a nearby garden. Seconds later, it is lobbed out again, straight back onto the pitch.

On the sideline, Mohammedan supporters clap excitedly. They stand around shouting encouragements in English and a smattering of Sylheti. “Come on boys. Get the ball!” one yells. “He’s out of control. Kitha korer be! [What is he doing]” another hollers. “Hit it! Hit it! Shoooot!” To everyone’s surprise, it is not long before no 7 of the Mohammedans scores the first goal of the match.

As the game rages on, an older man gently pushes a shopping trolley with Bombay Mix for sale along the edge of the pitch. He keeps an eagle eye on the ball, careful to jump out of the way if it comes hurtling towards him. I stand next to some pundits who are discussing tactics. “He doesn’t attack as much, does he?” “Well I suppose he’s accepted his position. With all due respect, he’s not as good as he used to be.”

“It makes a difference to get the first goal of the match,” Juel Miah says, pleased with the way his side is playing. A central mid-fielder, he is currently out of action due to injury. He says that the Mohammedan is a legendary team, likening it to the Manchester United of the British Bangladeshi Football League. A few years ago however, there was turbulence as the older players began retiring and the younger ones took over, but the fortunes of the team have stabilised since then.

“I’ve been a part of the team since I was sixteen. We’ve had good times and we have had really tough times. I love being in the team – the passion, the competitiveness. We have a really good set of friends. Any issues that you may have in your personal life, you forget them on the pitch. When you are playing, it could even be against your own brother – which in the past I have done – the important thing is that this team is your family. We have known each other for so many years and we look out for each other. Everyone sticks together. We have a really good bond.

I support Tottenham. When I was eight, I got the application and was due to try out for the team, but I didn’t go. At the time, British Bengalis didn’t think playing football could be a real job. This is changing a little with the current youth – some are really good players, but they don’t try to become professionals. Uni and education is what people focus on.”

Back on the pitch, one of the Mohammedans kicks the ball into the bushes to kill time. The game plan, one of the pundits explains, is to tire the reds out before giving them a chance to score. Though there is no swearing, the game is not always polite. Whilst tackling another player, no. 5 of the Hackney side is kicked in the leg and is on the ground. The match stops for a minute or two as the referee looks into it. The game resumes. Later, there is another slight altercation. “If you wana do it, we can do it, yeah,” a player challenges, throwing dirt from the pitch onto the back of an opponent. The ref. intervenes and has a cautionary word with them both. Seconds before the half time whistle is blown, the Hackney boys manage to squeeze a ball passed the net, leaving the Mohammedan goalkeeper stunned.

During half-time, over the prerequisite oranges and chewing gum, the manager gives a quick debrief. “Don’t get dragged down to their level,” he says, “you are better than they are.”

“The problem,” another says, “is that we get the ball, make a few passes but then it goes up straight into the air. For the final part, we need quality. As soon as you get it, look up.” The team looks pensive and nervous.

The heat is on in the second half. This time, the blues are on the offensive. With heart rates up at optimum, they narrowly miss out on a number of potential goals. Another one of the reds is down, but it is hard to know whether this is a diversionary tactic, playing for time or genuine. The injured writhes around on the ground, face in agony. The game is stopped again as the ref. sorts it out. Soon enough, the player is up and running.

At one point, the linesman awards a free kick to the reds. The ball is lined up and a powerful kick sees it flying in the direction of the Mohammedan’s goal. A player jumps to header it. Another throws his leg up into the air, outstretched in the same direction. The two look like they will have a meeting, but by the fraction of a second or the split of a hair, they manage to avoid a collision. The ball lands on the ground and finds itself in a tangle of legs, ever threatening and edging towards the goal. It is niftily thwarted.

“Keep pressing, keep pressing,” a fellow team mate barks. In the last few minutes, the Mohamedans score a second goal. The supporters clap jubilantly. A red striker, finding an opening, makes a final attempt, but it goes wide off the post. The final whistle is blown and the blues win, 2-1.

They don’t call it a game of two halves for nothing.

![EAST END FOOTBALL SERIES - by JEREMY FREEDMAN 2014_10]()

![EAST END FOOTBALL SERIES - by JEREMY FREEDMAN 2014_11]()

![EAST END FOOTBALL SERIES - by JEREMY FREEDMAN 2014_13]()

![EAST END FOOTBALL SERIES - by JEREMY FREEDMAN 2014_6]()

![EAST END FOOTBALL SERIES - by JEREMY FREEDMAN 2014_14]()

![EAST END FOOTBALL SERIES - by JEREMY FREEDMAN 2014_9]()

![East End Footballs Portraits by Jeremy Freedman 2014 Jamal - Ju - Omar - Iqbal - Sadique - Kamal - Nazrul by Jeremy Freedman 2.peg]()

Craig Tomkins, 25 - Striker, mid-field

I am a semi-professional football player, I signed up with the team earlier this week. This is my first game with them and I scored the first goal of the match. It gives you a boost to do so. I looked where the wall was and the keeper had no chance. I don’t understand Bengali but I’m sure I’ll pick it up. I am happy to bring my knowledge and ability to help and teach the other members.

![East End Footballs Portraits by Jeremy Freedman 2014 Jamal - Ju - Omar - Iqbal - Sadique - Kamal - Nazrul by Jeremy Freedman 21_3]()

Kamal Khan, 28 - Fall back, right

I joined the Mohammedans because it was my local team. I was fourteen and was part of the senior team by the time I was fifteen. It’s my second home. From a young age I wanted to stay fit and to see my friends. I think I will play a bit more and then I aim to coach. Our team needs a youth team to keep the legacy going so Iqbal, the goalie, and I have set one up. It helps to keep the kids off the streets as well, stops them from going astray. We have around sixteen to eighteen players and have to turn many more away.

![East End Footballs Portraits by Jeremy Freedman 2014 Jamal - Ju - Omar - Iqbal - Sadique - Kamal - Nazrul by Jeremy Freedman 21_6]()

Iqbal Hussain, 25 - Goalie

I’ve been part of the team for around ten years. I’ve always played in the same position, it is a very important role and one of the biggest responsibilities. It allows me to play to my strengths. It’s important to have a youth team to sustain the structure and the ethos of the team. We haven’t had this sort of structure in the past. It helps our senior team too with new players coming in, maintaining our reputation.

![East End Footballs Portraits by Jeremy Freedman 2014 Jamal - Ju - Omar - Iqbal - Sadique - Kamal - Nazrul by Jeremy Freedman 21_5]()

Sadique Ali, 28 - Left-wing and Manager

A friend introduced me ten years ago. The manager at the time tried me and I got into the B team. I slowly moved up to the A team. The team is a family, we have known each other for so many years. I played in New York some years ago and got the Most Valued Player award. I got lucky. I get a buzz from it. Last year we came fourth in the League and, if we can keep our players fit this year, we definitely have a chance of winning it.

![East End Footballs Portraits by Jeremy Freedman 2014 Jamal - Ju - Omar - Iqbal - Sadique - Kamal - Nazrul by Jeremy Freedman 21_4]()

Dmitri Larin, 25 - Centre back

The game was alright today. Although the team was not on-game in the first half, the second half was ours and we got a few more breaks. Eventually, I want to play professional football.

![East End Footballs Portraits by Jeremy Freedman 2014 Jamal - Ju - Omar - Iqbal - Sadique - Kamal - Nazrul by Jeremy Freedman 21_8]()

Raju Miah, 28 - Centre, mid-field

I haven’t been playing for four or five seasons. I’m taking a break as I have a groin injury, but I’m hoping to be back in the winter. I’ve been with the team since I was sixteen or seventeen. I have played for other teams in that time but I have always returned. I like the unity and friendships – we stick together. We have history and a lot of other sides envy us. We are trying to get non-Bengalis in to the team, but we also want to keep it local.

![East End Footballs Portraits by Jeremy Freedman 2014 Jamal - Ju - Omar - Iqbal - Sadique - Kamal - Nazrul by Jeremy Freedman 21_2]()

Melvin Simpson, 25 - Centre forward

It was a good game. I scored the second goal of the match. This is my first season with the team and I’ve already met a lot of interesting people. I usually play in the Uxbridge league, but playing in the summer league keeps you match fit for the winter.

![football group by Jeremy Freedman 2014]()

The Mohammedan Sporting Club

Photographs copyright © Jeremy Freedman